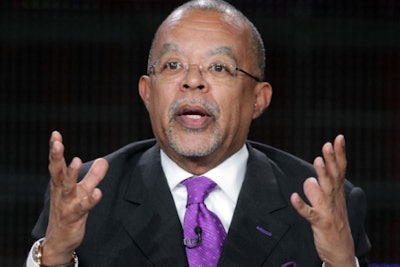

But when Harvard University announced last week that Dr. Henry Louis Gates Jr. had secured a $15 million gift from alumnus Glenn H. Hutchins to build a research center for African and African American Studies, the news was hardly met with unanimous enthusiasm in some quarters of Black studies.

While Gates—who is frequently referred to by his nickname “Skip”—hailed the creation of the Hutchins Center as “one of the greatest days in the history of African American Studies at Harvard or anywhere in the academy,” others were downright dismissive.

“I refer to Skip Gates as the Booker T. Washington of Black studies,” said Dr. Raymond A. Winbush, who directs the Institute for Urban Research at Morgan State University. “He commands most of his respect from White benefactors.”

Dubbed as one of the nation’s most recognized Black scholars, Gates has done what so many others have been unable to do: aggressively court wealthy donors like Hutchins and convince them to give generously to his growing academic empire, enabling him to operate at Harvard with an unparalleled degree of self-sufficiency.

“If you raise your own funds, you have a place at the table,” Gates said in an interview with Diverse.

“He is a charmer,” said Dr. Robert Hall, chairman of the department of African American Studies at Northeastern University, who has had a long-running feud with Gates. “His role is entrepreneur and many of us don’t function in that role or we don’t have the development apparatus at our schools to do what he’s doing at Harvard.”

As one Harvard administrator quipped in an interview, “What Skip wants, he gets,” she said with a laugh. “But to be fair, he’s a workhorse who never slows down. You have to give him that credit.”

By the late 1990s, Gates assembled his “dream team” by luring some of the most recognized Black scholars in the country to teach at Harvard. The roster included academicians like Drs. Cornel West, K. Anthony Appiah and Evelyn Higginbotham. West and Appiah have long since departed and Higginbotham replaced Gates as chair of the African American Studies department when he stepped down to focus his attention on the Du Bois Institute—a research entity that he founded in 1991.

Now, with the launch of the Hutchins Center for African and African Research, Gates has catapulted himself back on center stage to lead one of the largest research centers on a university campus.

And he scoffs at the critics who have the temerity to question why the center is named after a wealthy, White private equity investor who does not appear to have a grounding in Black studies.

“It’s a naming opportunity,” Gates said matter-of-factly. “If you put up the money, you get the building named after you. That’s how it works.”

But African-Americans have not always subscribed to that kind of reasoning, said John H. Bracey Jr., who chairs the W.E.B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

“There is a history that has to do with a recognition and participation in the struggle,” Bracey said, adding that the names of White abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison and Lucretia Mott have rightly been emblazoned on elementary school buildings populated by Black students across the country.

On the other hand, Blacks, he said, never gave much thought to the idea of naming Tuskegee University after Andrew Carnegie, even though the wealthy, White philanthropist donated millions of dollars to the Alabama Black college that was founded in 1881 by Booker T. Washington. “They said, ‘Thank you for giving the money.’ That was it,” Bracey said.

When the Hutchins Center finally opens its doors, it will house nearly a dozen programs and Institutes focused on Africa and the diaspora, including the Du Bois Institute. Other entities include Harvard’s Hiphop Archive and Research Institute, the Neil L. and Angelica Zander Rudenstine Gallery, the Hutchins Family Library, the Study of Race and Gender in Science and Medicine and the Ethelbert Cooper Gallery of African and African American Art.

Gates, who will serve as the founding director of the center, said that Du Bois—the first African-American to graduate with a Ph.D. from Harvard—will remain a central focus of the center’s work.

“Anyone who has a concern about the future legacy of Du Bois need not be concerned. We would be a fool to touch that legacy,” he said. “What this means is that, a thousand years from now, the study of African and African American Studies at Harvard will be guaranteed. What we have built under the rubric of the Du Bois Institute will continue to grow through the Hutchins Center with even greater global reach, in a way that would have made the public-minded Dr. Du Bois proud.”

Though the 63-year-old Gates has hailed Hutchins as a “visionary philanthropist” who has chaired the board of directors of the Du Bois Institute for the last decade, little is known about his interest and knowledge of African-American culture and history, though he was recognized with the “Breaking Barriers” Award earlier this year by the National Action Network, the civil rights group founded by The Rev. Al Sharpton.

Hutchins could not be reached for comment.

Given Gates’ status as a celebrity professor, some scholars have long lamented that he has held a stranglehold over the profession, particularly in terms of attracting dollars for Black studies program. Others have charged that, despite his championing the field, Gates hasn’t done enough rigorous scholarship.

Ishmael Reed publicly chided The New York Times for referring to the Harvard professor as the nation’s pre-eminent Black scholar.

“If Gates is the pre-eminent scholar of African American Studies, I’d hate to see those who are not pre-eminent,” said Reed. “He hasn’t written a scholarly work since the 1980s. Take a poll of African-American professors and he might come in at around 30.”

Gates seems undeterred by the criticism.

“I’m not the gatekeeper of the field,” he said. “I would hope that what we do here in Cambridge will further expand our marvelous field.”

It’s hard to argue with Gates’ productivity and the millions of dollars he’s brought into Harvard, operating almost as a lone fundraiser who works around-the-clock to reel in the dollars and a base of supporters who will continue to champion his causes.

At the launch of the Hutchins Center next week, Valarie Jarrett, senior adviser to President Obama, will receive the Du Bois Medal along with playwright Tony Kushner, U.S. Congressman John Lewis, Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor, director Steven Spielberg and David Stern, commissioner of the National Basketball Association.

“The W.E.B. Du Bois Medal is named for the great scholar and thinker who devoted his life to the serious study of African and African American history and culture,” said Gates, who is also the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor. “Dr. Du Bois, cosmopolitan in his taste and manners, worked tirelessly to produce and publish learning in all areas of the African diaspora, keenly aware of the need to bring this information to the public. This year’s Du Bois medals are presented to a most distinguished roster of recipients in the spirit of intellectual achievement and social engagement.”

Jamal Watson can be reached at [email protected].