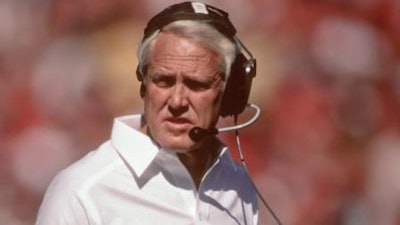

Former Stanford and San Francisco 49ers coach Bill Walsh is credited for the school’s track record of diverse coaching.

Former Stanford and San Francisco 49ers coach Bill Walsh is credited for the school’s track record of diverse coaching.Though Stanford University has a reputation for strong academics, there is another distinction to add to its repute: athletics. The elite private school’s record of coaching diversity in major sports over the last 25 years is hard to match.

Stanford has had three Black head football coaches, more than any other school in Division I, outside of HBCUs.

“I think it is a pretty big deal,” says Dr. Boyce Watkins, a scholar who has pushed for racial equality in NCAA sports. “If you consider the history of racism, I think a lot of schools would be hard-pressed to have had three Black football coaches.”

Currently, Stanford has both a Black football coach, David Shaw, and a Black basketball coach, Johnny Dawkins. Other than HBCUs, that combination in two revenue-producing sports is rare, though not unique.

The campus, located near Palo Alto, Calif., also boasts a Black athletic director, Bernard Muir. One of his two deputies, Patrick Dunkley, is African-American.

“Somebody in the athletic department at Stanford — maybe a group of people — have made diversity a priority,” Watkins says. “You can’t help but applaud that.”

Dr. Harry Edwards, who has pushed for “democratic participation” in college coaching since the late 1960s, credits former Stanford and San Francisco 49ers coach Bill Walsh for the school’s track record.

“I’m quite certain somewhere back there this is tied in some way to Bill Walsh’s influence,” says Edwards, who developed a close relationship with the late Walsh as a sports consultant to the 49ers beginning in 1985.

Walsh played a direct role in grooming each of Stanford’s Black football coaches.

The first, Dennis Green, worked twice as an assistant coach under Walsh at the 49ers. Tyrone Willingham was one of the first participants in a minority coaching fellowship program that Walsh and Edwards set up at the NFL team, a pioneering model the league later made mandatory for all the professional league’s teams. Shaw, Stanford’s current coach, actually played for Walsh after he returned to the school following his on-field leadership of the 49ers.

“That was where Bill Walsh and I came together, around making football not only what it could be both on and off the field but what it should be in a society as diverse as America,” Edwards says.

Diversity was a value Walsh promoted, Edwards says, on his teams and coaching staffs. When it came to elite academic schools like Stanford, Walsh also had a recruiting strategy in mind.

In conversations with Edwards, Walsh observed that, because of its high academic standards, “Stanford was not competitive in terms of getting the kind of Black talent that they had to have” to beat athletic powerhouses in the Pac-12 conference like the University of Southern California and University of Oregon.

Walsh outlined two possible solutions to the recruiting problem. One was to depart from regular admissions standards, bring in Black athletes unprepared for Stanford’s coursework and then provide them academic support during their first two years. That, Edwards notes, “Stanford absolutely refused to do.”

The other approach Walsh envisioned was to hire a coach who could successfully recruit from the smaller pool of Black high school seniors who excelled both at academics and athletics. Edwards said such a coach could comfortably visit those players at home, talk with their parents and maybe go to church with the family and talk to the pastor.

“All of that means a Black coach has somewhat of an advantage because he knows and understands and, in many instances, has been a part of the culture,” says Edwards.

It is unclear who Walsh spoke to at Stanford about the two recruiting strategies.

“I’m quite certain Bill had that conversation,” says Edwards. “I was not there. I could not speak to that, definitively. But I know Bill and I had that conversation, more than once.”

Green, an assistant to Walsh at the 49ers in 1979 and 1986-1988, was the first to test the recruiting advantage Stanford could have with a Black coach. He was hired at Stanford in 1989.

“When Bill left the 49ers, he made sure that Denny Green got a shot at that Stanford job,” Edwards says. “Bill wanted Denny to be at Stanford. He thought that would be an ideal place for both him and Stanford.”

In 1995, Stanford hired Willingham, who did not have any experience as a head coach. Five years later, Willingham took the team to the Rose Bowl — something Walsh had not achieved.

Walsh, the outgoing coach, did not believe the school should have only Black coaches — he had recommended promoting a White assistant instead.

At the time, Condoleezza Rice was Stanford’s provost. The athletics department reported to her when it came to its operations, budget and compliance issues. Rice has taken credit for hiring Willingham. Earlier, she sat on the Stanford committee that recommended Green as head coach.

In at least one case, Walsh’s recruiting strategy paid off for Willingham. Ed Smith, a former NFL player, went on four campus visits in 2000 with his son Alex, who played football at a Catholic high school in Denver. The last visit was to Stanford.

Ed Smith and his wife, Pia Dennis Smith, both graduated from selective private colleges, so strong academics were important to them. But it was Willingham’s trustworthy demeanor that sold the couple on Stanford.

“You could tell he was a very disciplinarian type [of] guy, a no-nonsense type of guy,” Ed Smith recalls. “I felt Tyrone Willingham was that type of a leader and a coach that really took the kids’ interest at heart.”

Alex Smith graduated from Stanford and started a professional career in football. He currently plays tight end for the Cincinnati Bengals in the NFL.

Shaw became Stanford’s football coach in 2011 after four years as offensive coordinator. He has led the team to the Rose Bowl two years in a row.

During the 2012 season, there were 120 head coaches whose teams were eligible to play in post-season bowl games. Fifteen of those coaches were African-American, two were Asian and one Latino, according to the latest Racial and Gender Report Card from the Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport at the University of Central Florida.

The number of Black football coaches at top schools has grown slowly since the 1980s. Because only slightly more than 40 African-Americans have ever held the job at a traditionally White college in Division I, Stanford’s record of hiring three stands out.

At least eight traditionally White universities have had two Black football coaches: Eastern Michigan, Louisville, Miami (Ohio), Michigan State, New Mexico, New Mexico State, Northwestern and UCLA.

Besides Stanford, at least a half-dozen universities have had Black football and basketball coaches simultaneously: Alabama-Birmingham, Buffalo, Eastern Michigan, New Mexico State, Temple and Washington.

“Stanford’s hiring practices have consistently shown that they are after the best coach available,” says Richard Lapchick, director of the Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sports. “Their record is remarkable and should be the standard for all schools.”

Although Walsh died in 2007, four years before his former player Shaw became coach, his influence appears to live on in Stanford’s athletic department.

“I think there’s a lesson in there for a lot more schools going forward,” Edwards says. “I think that Bill Walsh is still teaching.”