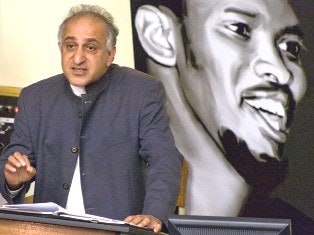

Saleem Badat, vice-chancellor of Rhodes University, is set to become the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation’s first program director for international higher education and strategic projects.

Saleem Badat, vice-chancellor of Rhodes University, is set to become the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation’s first program director for international higher education and strategic projects.Prior to 1994 when South Africa abolished apartheid and became a democracy, enrollment rates by race and ethnicity at the nation’s colleges and universities were woefully askew.

Specifically, in 1993, Africans in the country accounted for just 40 percent of all college students, even though they represented 77 percent of the population. White South Africans, on the other hand, accounted for 48 percent of all college students, even though they comprised just 11 percent of the population.

In contrast, by 2011, Black students represented about 81 percent of South Africa’s postsecondary student population of 938,200 — a number nearly double the 473,000 that it was in 1993, according to figures obtained by Diverse.

But even though overall Black enrollment in South Africa’s colleges and universities is up since the days of apartheid, one leading scholar says the raw numbers mask a series of other disparities that plague the nation’s institutions of higher learning.

Those disparities include high attrition rates for Black students, and underrepresentation in the STEM fields and business and commerce, according to Saleem Badat, vice-chancellor of Rhodes University in Grahamstown and a scholar who has written extensively about issues of access, diversity and success in higher education in South Africa.

Participation rates for Blacks in South Africa have remained stagnant over the past two decades. Badat notes that whereas participation rates for Africans and Coloureds stood at 9 and 13 percent, respectively, in 1993, as recently as 2007, they stood at 12 percent for each group.

The participation rate for Whites and Indians, on the other hand, stood at 40 and 70 percent, respectively, in 1993. Fourteen years later, those rates were 43 and 54 percent, respectively. Badat says the reason that participation rates for Blacks in South Africa have remained stagnant is not solely because of the nation’s legacy of apartheid.

“While the apartheid legacy continues to weigh heavily on contemporary higher education, South Africa’s higher education problems and shortcomings are not rooted entirely in the apartheid past,” Badat said in a paper he wrote about South Africa’s 20th anniversary as a democracy for a February seminar at the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, where later this year he is set to become the foundation’s first program director for international higher education and strategic projects.

“Both in higher education and more generally, the state and key actors appear to lack the will to act courageously and decisively at the levels of policy, personnel, and performance when it is clear that problems remain intractably entrenched,” Badat wrote.

Government efforts

It’s not as if the South African government is completely oblivious to its higher education issues.

For instance, in a 2014 White Paper issued by the Department of Higher Education and Training, the department states its commitment to “progressively” introduce free education for the poor at South African universities “as resources become available” — the implication being, of course, that presently those resources are not available.

It also speaks of increasing overall participation rates within universities from the current 17.3 percent to 25 percent — or from just over 937,000 students in 2011 to about 1.6 million enrollments in 2030.

Badat says the paper is, like many other South African policy documents, “expansive in vision but extremely short on details.”

South Africa’s National Planning Commission has also acknowledged a number of problems in the nation’s higher education system.

“Many individuals with poor schooling aspire to higher qualifications, but they are academically less prepared than their middle class counterparts,” the plan commission states in its National Development Plan 2030. “Support programs should be offered and funded at all institutions.”

It also talks about how schools at the pre-college level can be “intimidating for many parents of learners.”

“In poor communities in particular, there is an imbalance in power relations,” the paper states. “Parents often feel ill equipped to engage with teachers and school management about the performance of their children and the school as a whole.”

But then there are those real-life human stories that don’t comport neatly with the explanations and analyses of policymakers and experts.

Consider, for instance, the story of 22-year-old Vuyile “Lucky” Sixaba.

Even though Sixaba attended “impoverished township schools that remained deeply disadvantaged from years of apartheid,” Sixaba managed to distinguish himself and won a full scholarship to Rhodes University from the Square Kilometre Array Africa global collaboration, which is part of an international group attempting to build the world’s biggest radio telescope.

“The scholarship really made life easy for me in university,” Sixaba said in an article on the Rhodes University website.

Sixaba graduated from Rhodes University this past April with a bachelor’s of science degree after having completed a triple major in pure math, applied math and mathematical statistics.

One of the reasons the university celebrated his story is because Sixaba’s mother works as a groundskeeper there.

Interestingly, Sixaba’s mother made a bold move out of frustration when she saw him going astray academically as a child; that move ultimately put Sixaba on the road to college.

“It’s only when my mother got sick of being called to school for me making trouble that she told my math teacher that he should beat me if I do something again,” Sixaba said in an email to Diverse.

“After that, I listened in class and worked hard at home with my studies, studied with a friend of mine who always had a ‘mind for school,’” Sixaba explained. “That year [grade 9] I happened to come out top of my class in every subject.”

Sixaba noted that beating students is not legally sanctioned in South Africa.

“I guess it was just for me to be in fear, and it worked, you know,” Sixaba said. “I highlight it as one of the best things that she’s done for me. It really turned me [in] to another person.”

Equalizing access

In South Africa, as per a 1997 Department of Education paper, institutions of higher learning are required to “develop their own race and gender equity goals and plans for achieving them, using indicative targets for distributing publicly subsidised places rather than firm quotas.”

Badat, in an essay he wrote for a 2012 book, Equalizing Access: Affirmative Action in Higher Education in India, United States, and South Africa, noted that many universities in South Africa do not have an admissions policy.

While the issue of affirmative action in South Africa is a “contested” one, according to Badat, Sixaba says he and his fellow college students never discussed issues of admissions or affirmative action.

“I really don’t believe in those ‘special policies for Black people,’” Sixaba said. “I feel like it’s also a way of discriminating against us. Nobody is better than anybody else.

“…In terms of entering higher education, I don’t think anyone should be given an edge over anybody else,” adds Sixaba. “We all have similar brains, whether you are Black, White, green or purple.” Badat is of the mind that bolder action and measures must be undertaken to bring about greater equity in access, opportunity and outcomes in higher education.

“This is a tragic waste of the talents and potential of individuals from socially subaltern groups — from amongst who may be another Albert Einstein, Marie Curie, Angela Davis or Nelson Mandela,” Badat told Diverse via email. “It also compromises democracy, which usually proclaims the promise of greater equality and a better life for all people.”