(Source: GoCollegeNow.org)

(Source: GoCollegeNow.org)Supporting first-generation students is a priority that many institutions have identified but not many have mastered.

Former Columbia University senior admissions officer Jaye Fenderson said that, at Columbia, she realized not only how fortunate she herself had been in being able to attend Columbia, but that there is “an opportunity inequality at our top-tier institutions across this country” that means that “higher education demographics are not representative of our population.”

Fenderson left Columbia to pursue a career in film, with her most recent production, First Generation, focusing on this opportunity disparity at institutions around the country.

At a recent presidential roundtable hosted by the George Washington University Law School, Dean Blake Morant asked panelists a question: “How do we ensure that we are providing an opportunity, particularly to those [first-generation] students who may not traditionally have college in their sights, because I see this as an endemic part of the world that we are now living in?”

Rutgers University-Camden Chancellor Phoebe Haddon said for her, a fourth-generation college graduate, it was “striking” to her to find people who still ask if there’s value in higher education, but said that she was “quickly baptized” by some of the challenges facing first-generation students once she arrived at Camden.

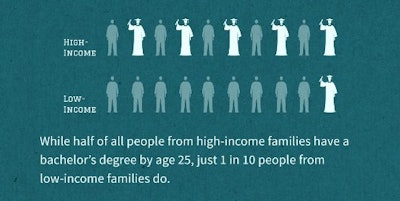

“What I know now is that, if you come from a family where there has not been a high school diploma, you are only about 5 percent likely to be able to go on to college. And so we’ve got to intervene in that distressing number,” Haddon said.

It isn’t as easy as it might sound.

“How you intervene, what kinds of interventions work is a different story, but the fact of the matter is that that’s the case, and it’s the case that’s more pronounced for me because I’m in the city of Camden, where the [community college enrollment] is about 10 percent and the level of opportunities for people have been very, very small,” Haddon said. “So what I am concerned about is how we move those numbers.”

Fenderson said the conversation about moving the numbers has to include those the numbers represent. “It’s not just enough to talk about the [disparities] among people that already know about it; we have to find a way to get that information out to the people that need it,” she said. “Sometimes it’s good to hear from real voices and not just look at statistics and numbers.

“First and foremost, students don’t know what they don’t know,” she said. “There’s this deficit of knowledge” for first-generation students around access and opportunities in higher education. For example, she said, “Coming into the college admissions process as a senior is really too late.”

Hampden-Sydney College President Christopher Howard said institutional mindsets must change in order to better serve these students.

“Institutions have to have a mindset to … meet you where you are to get you where you need to go,” he said, adding that is true whether students are “first-generation, of lower socioeconomic strata, racial minorities [or otherwise having] a unique set of circumstances, being mindful of that I think is the first part.”

Haddon said, “The mindset is one thing, but a clearly defined mission that all administrators and faculty wrap around [that says] if we are going to be devoted to first-generation students and we are looking to make sure that they succeed, then our mission is to get them through and the resources that we have to be devoted to that, so that means that some of the things that we would love to do, we cannot do, because we are mission driven.”

In a similar vein, it is critical to realize that “money is very, very important. Resources are the lubricant to get things done,” Howard said, and the allocation of those resources says a lot about an institution’s commitment to various issues.

For many first-generation families, Fenderson said, there is “a misunderstanding of the cost of college.”

“I think all of us who work in the education field know that students aren’t paying the sticker price for college,” Fenderson said, saying schools who want to be committed to serving first-generation students need to do a better job of conveying the “messages of college affordability,” which she said “are not trickling down to first-generation families.”

Former CUNY and University of Cincinnati President Greg Williams said that it is important for institutions to not only recognize the major challenges facing first-generation students, but set clear goals to support them.

“It’s very clear that the highest dropout rate of any group in college is first-generation students,” he said. “As we get these first-generation students that come in, we have to make sure they’re clear what that focus is and we have to keep them on track, because the longer it takes, the less likely it’s going to happen for them.”

“One of the things we did at Cincinnati is we put together a Gen One House, where we had first-generation students that lived together for an entire year with counselors and others who really controlled the tutorial period. Over a terminal period, we had basically a 90 percent graduation rate for the folks that had gone through the Gen One House,” he said.

Messages that encouraged students to enjoy their time, however long it lasted, or that encouraged flexible scheduling like gap years or semesters, can be detrimental to these students, Williams said.