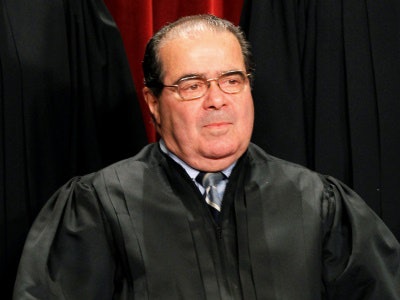

Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia

Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia

h

As President Obama encouraged Americans to push back “against bigotry in all its forms” during his remarks commemorating the 150th anniversary of the 13th Amendment Wednesday, Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia made waves with his remarks about the abilities of African-American students in this country during the oral arguments of the Fisher vs. University of Texas at Austin case.

Referencing what is commonly known as the mismatch theory ― the idea that by admitting students of color through affirmative action an institution is actually setting these students up for failure, because they will inevitably fail to meet the stringent academic standards set by the institutions ― Scalia said, “There are those who contend that it does not benefit African-Americans to to get them into the University of Texas where they do not do well, as opposed to having them go to a less advanced school, a … slower track school where they do well.”

Scalia went on to allude to the high success rate of historically Black institutions in graduating African-Americans in critical fields, saying, “One of the briefs pointed out that most of the the Black scientists in this country don’t come from schools like the University of Texas. They come from lesser schools where they do not feel that they’re being pushed ahead in classes that are too fast for them.”

Scalia then went on to suggest that “Maybe [the University of Texas] ought to have fewer [Black students,” not more, because “maybe … when you take more, the number of Blacks, really competent Blacks admitted to lesser schools, turns out to be less. … I don’t think it stands to reason that it’s a good thing for the University of Texas to admit as many Blacks as possible.”

Northeastern University doctoral candidate and a frequent writer on race Theodore R. Johnson III called this theory “incomplete at best.”

“According to the theory, students receiving racial preferences for admission are unprepared for the academic rigors and, as a result, are more likely to change majors or drop out,” Johnson said. “This may be true, but it doesn’t account at all for the support structure of the university for minority students. If there are no black faculty members, advisors, or academic counselors, then it’s almost to be expected that black students with little descriptive representation in the university are more likely to struggle in rigorous majors.”

“This isn’t a commentary on the intellect of the students, but the lack of representation at the university,” he added.

Dr. Richard Reddick, a professor in the College of Education at the University of Texas at Austin and himself a graduate of the institution, said the idea is “a trending pet theory among conservatives.” He said he found Scalia’s remarks “shocking,” but he recognizes that “the idea is out there.”

“I think it comes from a White supremacist notion that White students are the norm and are supposed to be at elite institutions, while students of color are automatically scrutinized in those same spaces,” he said.

Reddick said the social structures in place at the majority institutions are unfavorable to Black students.

“While all students experience challenges transitioning to college, White students aren’t navigating the same structural and societal impediments that many students of color do. … We’re seeing the impact of those experiences on campuses across the nation. I wonder how the activists involved in Concerned Students 1950, for example, fared this semester in class, while they were challenging the University of Missouri to better support Black students, staff, and faculty?”

“I have certainly experienced this on a personal level,” he said. “Students of color are marked as other ― of course, de jure and then de facto segregation outright kept Black and Latino students out of elite PWIs for years.”

Johnson said, “HBCUs produce more doctors, lawyers, engineers, etcetera because they have resources that speak to the specific challenges of Black students. … The theory doesn’t adequately account for the factors outside the classroom that impact performance inside it.”

“If there is a mismatch, it’s in the faculty members more than it is in the academic material, in the support structures, not the academic abilities of Black students,” Johnson added. “The reason it doesn’t happen as much to White students is because the very competitive university is structured to support them in a way it isn’t for Black students.”

Reddick said he thinks the idea of the mismatch gains traction despite its tendency “to discount structural and environmental factors and attempt to quantify admissions criteria” because “it is likely very comforting to think that there are a set of metrics that equate to a “yes” or a “no” admissions decision.”

“But most of our decisions of consequence involve many factors. We don’t simply award jobs to people based on their class rank and test scores,” he said. “We want to know how they navigate adversity, if they are effective leaders, how well they engage with colleagues. We also acknowledge that some pathways are more challenging than others. Everyone is familiar with Bertrand and Mullainathan’s study that demonstrated that resumes with White sounding names generated more callbacks than identical resumes with Black sounding names ― suggesting that racial discrimination still plays a significant role in economic opportunity.

Reddick said he is also “struck by this idea that all students are expected to have high grades. In Texas, the past two former governors released their undergraduate transcripts from elite universities ― Yale and Texas A&M. Both of them were solidly C students, but they are examples of the benefits of considering students in their entirety. Both were outstanding student leaders, and those attributes and networks clearly catapulted them to very successful careers in politics and business.”

“Imagine if it was argued that these two were a poor match for their universities! It’s been long established that success post-college is not simply correlated to academic performance; establishing leadership skills and networks. President Bush even made this exact point at a commencement speech at SMU last May: ‘as I like to tell C students, you too can be President,’” Reddick added.

Reddick said the entire crux of the Fisher case represents a huge difference in the opportunities for Black versus White students in this country.

“I think we need to examine the sense of entitlement that motivates this case,” he said. “Having a dream to attend a certain university, and citing the fact that your dad and sister went there, and you wanted to continue the tradition glosses over the fact that many students of color don’t have the benefit of having a college-educated parent, or any family tradition of college-going.”

“Of course, the plaintiff went on to LSU, a fine school, and performed quite well. Furthermore, she was extended the opportunity to attend a UT system school and potentially transfer, which many students of all racial backgrounds have done. She opted not to – the opportunity she found at LSU was a good fit for her,” he added.

Johnson said the idea of student success on any campus boils down to the idea that “For the typical student of any race, support mechanisms need to be in place to help them through the rigors of higher ed. … Some of them, the very exceptional, may not need the support, but most 18 year olds do.”