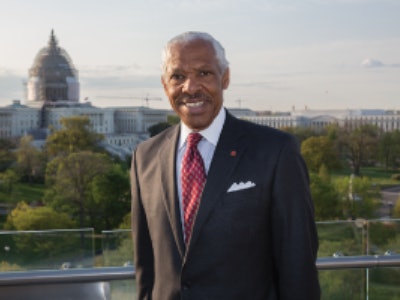

Leonard Haynes first came to the Department of Education in 1989 when George H.W. Bush tapped him to be assistant secretary for postsecondary education—the first African-American to hold the post.

Leonard Haynes first came to the Department of Education in 1989 when George H.W. Bush tapped him to be assistant secretary for postsecondary education—the first African-American to hold the post.WASHINGTON ― In a packed auditorium at the U.S. Department of Education, surrounded by many of those who say they know him as an adviser, fixer, friend, mentor, advocate, colleague, and surrogate, Leonard L. Haynes III, Ph.D., wrapped up nearly three decades of public service in higher education.

Former and present HBCU presidents, senior federal administrators, state government officials, corporate leaders, and even fraternity brothers, including William R. Harvey, Archie M. Griffin, Carrie Billy, Freeman Hrabowski, Ernest McNealey, Helga A. Greenfield, and Isiah Leggett, Ron Mason, and Haywood L. Strickland, were among the more than 100 guests who paid tribute to Haynes, who retired Monday from the Department of Education as senior director of institutional service for the Office of Postsecondary Education.

Dr. Louis W. Sullivan, president emeritus of Morehouse School of Medicine and a former secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, emerged as a “surprise guest” on the stage to thank Haynes for his contributions to the Department of Education. He urged Haynes, his former federal government colleague, to continue to “make the future of our young people and the nation brighter.” And in a stirring videotaped message, Norman Francis, the president emeritus of Xavier University, recalled how he’s “watched” over the years as his “friend, colleague and fellow educator” lifted others as he climbed. But like the long list of speakers that day, Francis called Haynes, a graduate of the historically Black Southern University, a champion of HBCUs.

Haynes, a long-serving political appointee, first came to the Department of Education in 1989 when George H.W. Bush tapped him to be assistant secretary for postsecondary education — the first African-American to hold the post. He also directed the Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education and was executive director of the White House Initiative on Historically Black Colleges and Universities. In this interview, Haynes reflects on his roots in learned family, his passion for Black colleges and what awaits him after retirement.

Q: Coming from a family of educators and college-educated people, did you have an idea of what you wanted to do for a career when you entered college?

A: Yes. I knew that I wanted to be around a college or university setting. That thought was in my mind as early as the fifth grade. I’ll never forget this; my parents gave me a new notebook to start the school year in Orangeburg, S.C. On the cover of the notebook were the pennants of U.S. colleges and universities. There were no Black colleges among them, but I was fascinated with the cover. I spent time looking up each of the schools and where they were located, and, before long, I was thinking, ‘I want to be a part of this.’ Of course, my Dad and Mom were influential in my decision to go into education. I wanted to follow in their footsteps.

Q: What have been the best aspects of being a public servant?

A: There’s a clause in the preamble of the United States Constitution that says “to promote the general welfare.” For me, that clause resonated in terms of government and promoting the general welfare of the citizens of the country, especially those who view society from the bottom up. I consider that the purpose of the government. I’ve felt honored and privileged to be in the service of the United States of America.

Q: You began your federal government career in the George H.W. Bush administration. How would you describe the plight of HBCUs then compared to now?

A: During his administration, there was a great deal of excitement about what was possible for HBCUs and how they could benefit from federal government support. President Bush, like presidents before him, signed the executive order in support of HBCUs, but he added an important dimension that established a presidential advisory board on Historically Black Colleges and Universities to the White House Initiatives on HBCUs. Dr. James Cheek, then the president of Howard University, served as the chairman of that board. It was widely recognized that HBCUs were limited-resource institutions, however, they had tremendous potential. I felt that, if we could marshal the resources of the federal government along with the private sector to benefit HBCUs, they could do so much more.

Q: So, how would you describe the plight of HBCUs now, compared to that era?

A: Unfortunately, the current administrative approach to helping HBCUs has been wanting and a near disaster. HBCUs, in terms of overall support from the federal government, have gone backward, not forward.

Q: Where is that most evident?

A: You can document it; look at the Parent Plus Loan debacle that cost HBCUs $168 million in operating capital or the lack of contracts and grants going to HBCUs because the executive order signed by Pres. Obama has not generated the kind of results that were hoped for. Actually, there has not been any movement of the needle forward.

Q: Does the responsibility for that lack of movement forward also lie with the now former Secretary of Education, Arne Duncan?

A: He was more focused on K-12 than on HBCUs and higher education. He said a lot of things, but actually doing something to advance and support HBCUs wasn’t a priority of his. Some of the other federal agencies may step up, but I’m not optimistic about that happening either.

Q: Looking forward, in a decade, what would you title the next chapter of the country’s historically Black colleges and universities?

A: That’s a tough question. But like I always say, if Black colleges didn’t exist today, they would have to be created. That’s because they are meeting unmet needs. No other set of institutions has a demonstrated commitment to the uplifting of a race of people who have been left behind and ignored. HBCUs are connected to the experiences of this country; they just need to be supported. I see an important role for them to continue to play in the 21st century. People say they are going to be out of business, but I don’t think so. Sixty percent of freshmen currently enrolled in the majority of HBCUs are the first in their family to go to college and that includes at Howard University. You would think that today, and at this point in my career, we would be talking about the second generation of students and college enrollment, but were not. This tells me, there is still a need for Black colleges.

Q: When you consider plans for life after retirement, how much will HBCUs and issues of college access still be a focus?

A: A lot of that will continue to be my focus. I’ll use this verse from scripture, 1 Corinthians 14:8, which was drilled into me by the late Dr. James Cheek, the former president of Howard. It says, “If the trumpet makes an uncertain sound, who will be prepared for the battle?” The trumpet is still blowing out here and there are a lot of uncertainties. Somebody has to be prepared to do the battle. I am leaving the Department of Education, but I am not leaving the battlefield because there is too much left to be done. I will always lift up HBCUs whenever I can and be critical when necessary. I’ve got to make a critical contribution while I’m still living.