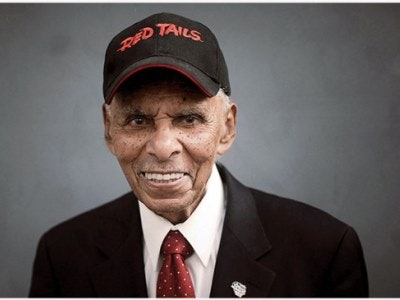

Roscoe C. Brown

Roscoe C. BrownAs commander of the 100th Fighter Squadron of the 332nd Fighter Group — better known as the Tuskegee Airmen, an all-Black segregated fighting unit during WWII — Roscoe C. Brown will forever be remembered for the battles he fought in the sky.

In the world of higher education, Brown will also be remembered for the forays he made on behalf of diversity in the realm of academe and access to higher education.

Brown — the longtime director of the Institute of Afro-American Affairs at New York University (NYU) and the longest-serving president at Bronx Community College — died over the Fourth of July weekend at Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx. He was 94.

“It is with a heavy heart that I share with you the sad news of the passing of Bronx Community College’s (BCC) distinguished President Emeritus, Roscoe C. Brown, Jr.,” President Thomas A. Isekenegbe said in a statement to Diverse.

Isekenegbe said Brown created programs to increase outreach to Bronx junior high and high schools and to support minority students going into science careers.

“During Dr. Brown’s tenure at BCC, more than 10,000 students graduated, going on to further their education and careers,” Isekenegbe said.

He noted that, in 2000, the building that houses the cafeteria, bookstore, student government and other student-oriented offices was named the Roscoe C. Brown Jr. Student Center.

He said the American flag will be flown at half-staff at Bronx Community College campus in honor of Brown’s life, service and inspiration.

Brown also was recalled fondly for his time at NYU.

“He is a founding father of the Institute of African American Affairs,” said Linda Morgan, administrative assistant for the institute at NYU.

“He was — and is to this very day — a very foundational person that believes in civil rights, humanity, our country,” Morgan said. “He’s a real pioneer.”

Brown chronicled the story of the creation of the Institute for Afro-American Affairs, as it was then called, in an article that appeared in The Journal of Negro Education in the summer of 1970. He was a professor of education at the time.

“The Senate of the New York University, responding to the atmosphere of concern that followed the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., passed a resolution of commitment to the concept of the development of an Afro-American Institute in Honor of Dr. King,” the article states.

The institute became a reality in 1969. It was meant to deal with the “harsh realities of the conditions of black people in America and disenchantment of black students with contemporary University life,” Brown’s article states.

“The major objectives of the Institute will be the identification and analysis of the contributions, problems, and aspiration of Americans of African descent and the development of skilled and committed students,” the article continues. “These objectives shall also relate to Puerto Ricans, Mexican-Americans and American Indians.”

Brown spoke fondly of his time at NYU.

“One of the reasons I was pleased to be at New York University was because it was a place of opportunity,” Brown, who earned a master’s degree and a Ph.D. from the Steinhardt School of Culture, Education and Human Development at NYU in 1949 and 1950, respectively, said in this NYU video.

“No, I didn’t experience racism,” Brown said of his time at NYU. “As a matter of fact, I was the antidote to racism.

“I believe that excellence overcomes discrimination. I believe that excellence gives you opportunity to make a change.”

Brown said he was seen as a professor who was a leader as opposed to a “Black professor.”

“And that was part of the culture at New York University,” Brown said. “The strength of NYU has been its diversity — diversity of ideas, diversity of opinions, diversity of faculty, diversity of students.”

After serving at NYU for 27 years, Brown became the third president of the Bronx Community College in September 1977. He held the position until June 1993.

During his tenure, the college “intensified its outreach to New York City’s economic and educational institutions through partnerships with business and industry to better ensure the success of graduates,” a brief description of his presidency states. “New programs were developed in high growth professions in the fields of health, technology and human services.”

Brown later served as director of the Center for Urban Education Policy at the Graduate School and University Center of the City University of New York (CUNY), where his work focused on the role of school-based management and parental involvement in school reform.

“He has served as an informal mentor to numerous presidents, especially those new leaders of color in the CUNY system, the largest urban system in the country,” states a profile that appeared in Diverse. “He has reached out to and supported presidents throughout the country.”

In the profile, Brown stated that his accomplishments were merely an extension of those who came before him.

“I stand on the shoulders of many people,” Brown said in the 2013 article. “Mary McLeod Bethune, Paul Robeson, Dr. Du Bois, my own father are the shoulders I stand on.”

Indeed, Roscoe Conkling Brown Jr., was born on March 9, 1922, to college-educated parents, according to a book tilted African Americans in the Military.

His father, Dr. Roscoe C. Brown Sr., held a degree in dentistry from Howard University and served as director of the Negro Health Movement of the U.S. Public Health Service and served in President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “Black cabinet,” the book states.

His mother, Vivian Kemp Brown, served as a schoolteacher. She held a degree from Virginia Union University.

Through their parents, Brown and his siblings met civil rights luminaries such as Du Bois and Bethune.

But it was a childhood trip to the Smithsonian Institution — where a 5-year-old Roscoe saw the Spirit of St. Louis, the plane in which famed aviator Charles Lindbergh made the first trans-Atlantic flight — that inspired Brown to want to fly.

Brown ultimately became a premed major at Springfield College and graduated with honors in 1943.

“Three days later, with the nation at war, he was called to active duty in the army,” the book about Black military leaders states. “He had heard about the 332nd Fighter Group, consisting of three squadrons of African-American pilots, which was training for assignment overseas.

“Knowing that prior to this war African-Americans had been barred from flying military plans and wanting to be part of aviation history, he resigned his Army Reserve commission and enlisted in the Army Air Force.”

He was sent to Tuskegee Army Air Field, a facility built in Alabama specifically to train Black pilots, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Much of that history made its way to the silver screen, the latest example being Red Tails, a 2012 film for which Brown served as a consultant to ensure historical accuracy.

Brown won numerous awards, including the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Congressional Gold Medal for his role as a Tuskegee Airman.

“He provided a really exemplary role about leadership and how to conduct oneself, how to communicate so that it can reach all channels” Morgan, of NYU, said of Brown, who for many years also hosted African American Legends, a public affairs show produced by CUNY TV.

“He paved the way I would say for African-Americans in academia as well as Africans in the diaspora at large,” Morgan said.

Jamaal Abdul-Alim can be reached at [email protected] or follow him on Twitter @dcwriter360.