Following Dr. David Holmes Swinton’s retirement last week as president of 141-year-old Benedict College, he and his wife, Patricia, are taking a long, 45-day vacation.

And then he plans to return to the retirement home that he built eight years ago in Columbia, South Carolina, and to quickly turn his attention to his first love: researching, writing and speaking about public policy issues that impact African-Americans.

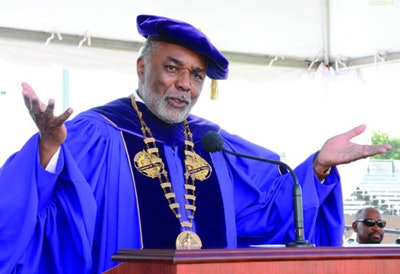

Dr. David Holmes Swinton advises aspiring HBCU presidents: “Be very sure about why you want to be an HBCU president. You can’t do it just for pay or prestige, because you won’t be successful.” (Photo courtesy of Benedict College)

Dr. David Holmes Swinton advises aspiring HBCU presidents: “Be very sure about why you want to be an HBCU president. You can’t do it just for pay or prestige, because you won’t be successful.” (Photo courtesy of Benedict College)“As president emeritus, I really don’t have any major duties,” Swinton says with a chuckle in an interview with Diverse shortly before his June 30 departure. “The president emeritus job, I guess, is to look old and act cute.”

Just talk to faculty, students and administrators at Benedict College, and it becomes increasingly clear that Swinton will be missed. He is a fixture at the institution and it’s easy to understand why.

The no-nonsense administrator has been at the private, Baptist-affiliated historically Black liberal arts college for 23 years, making him the longest-serving president in the school’s history.

College administrators say that after more than two decades of service, he has earned the right to relax and spend time with his eight grandchildren who live about two blocks away from Swinton and his wife.

“I did plan for this to be my last professional job if it was successful,” says the Harvard-trained economist of his time at the college. “I intended to retire from this position.”

Indeed, Swinton has had a prolific and distinguished career, having worked in a number of academic jobs before landing the top position at the storied college, which was founded by northern Baptists in 1908 and has retained its affiliation with American Baptist Churches USA.

Throughout his tenure, Swinton has achieved some major feats, including more than doubling the school’s enrollment to 3,140 students, which is the largest at any point in the college’s history.

“We’ve been busy,” says Swinton, adding that his effort to recruit more African-American males to the college has also been successful. “We’ve renovated almost everything on campus, at one time or another.”

Born in New Haven, Connecticut, Swinton moved to Timmonsville, South Carolina, as a young child and then relocated to New York City at the age of 12. Although he grew up in New York, earning a bachelor’s degree from New York University in 1968, and later moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he earned master’s and doctoral degrees in economics from Harvard University, he has a special place in his heart for South Carolina.

“I always considered South Carolina my home,” says Swinton. “This is where my roots are and where I developed the values that really kept me going.”

After working as a college professor and distinguishing himself as a prominent researcher whose focus is on the economics of African-Americans in the nation, Swinton’s foray into college administration was somewhat fortuitous.

He was recruited to Clark Atlanta University, where he served as the director of the Southern Center of Studies in Public Policy and taught economics. Later, he was recruited to Jackson State University, where he spent seven years as dean of the School of Business.

Committed to an ambitious public policy research agenda, Swinton was initially hesitant to go into academic administration, but then he realized that, as an academic leader, he would have “more control and influence” than he did as a research director.

In that role, he successfully led the effort to gain AACSB accreditation for the business school.

At his first convocation at Clark Atlanta, Swinton remembers that he was blown away by witnessing the faculty, dressed in full academic regalia, proudly singing the Negro National Anthem. He had never experienced anything like that before.

“That always made me cry,” he says of that celebratory occasion. “I felt like I was home.”

That love for HBCUs and their mission continued after Swinton was recruited to lead Benedict in 1994. It was during his time at Benedict that he discovered that his own father — who could not attend a non-HBCU in the South because of Jim Crow laws — transferred to the institution from another HBCU during his junior year.

Born during World War II, Swinton says that he developed an early interest in interrogating the challenges that beset African-Americans. And once he moved into the HBCU space, he was able to spend time addressing many of those issues head-on.

“I was always very interested in the problems of inequality and poverty,” says Swinton. “Economic disparities was always my major interest in economics.”

His passion for HBCUs remains strong, although he worries that public support for these institutions may be waning.

“People are not as concerned about integration anymore. That is one of our challenges,” says Swinton. “Many people believe that the predominantly White institutions are higher quality and that’s a challenge that we have to overcome.”

The mission of HBCUs is under attack, he says.

“We have a lot of top kids here too, but our mission is to expand educational opportunities for African-Americans,” says Swinton, adding that a majority of Benedict’s students hail from financially disadvantaged backgrounds. “I’m always optimistic because I believe we can overcome by hard work and courage and, if we continue to fight the battle, we will continue to survive for another 150 years.”

He dismisses those who claim that HBCUs are no longer relevant.

“We are needed as long as there are substantial and measurable differences between the socioeconomic status of Black Americans and other Americans,” he says. “Those gaps are still wide. They still exist and they are not shrinking.”

Jamal Eric Watson can be reached at [email protected]. You can follow him on Twitter @jamalericwatson

- This story also appears in the June 29, 2017 print edition of Diverse.