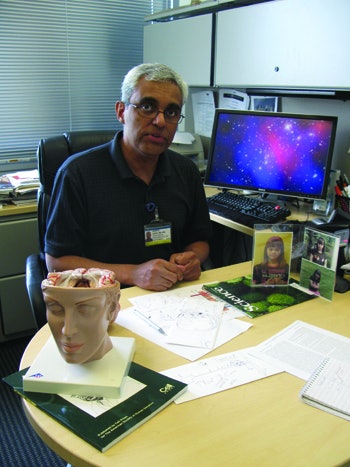

Dr. Alberto Costa’s research on Down syndrome was inspired by his daughter’s diagnosis.

Dr. Alberto Costa’s research on Down syndrome was inspired by his daughter’s diagnosis.AURORA, Colo. — Dr. Alberto Costa’s discovery that a drug might help the memory of people with Down syndrome was more than just a breakthrough for him as a scientist.

His daughter, Tyche, was born with the chromosomal condition 17 years ago. The clinical trial that he recently completed, producing cautiously encouraging results about a drug called memantine, was part of a journey that began with her birth.

Costa found that little brain science had been done on people with the abnormality. There was a “huge focus,” he says, on preventing their births. His wife, Daisy, had declined the pre-natal testing that might have uncovered Tyche’s condition because testing had spurred a miscarriage of a previous pregnancy.

The birth of Costa’s daughter, named after the Greek goddess of fortune and chance, wound up reconfiguring his life and his career.

Tyche became his inspiration, and Down syndrome and the brain, the focus of his research. It was a switch, but not a drastic one, from what he was doing when she came along—research at Baylor University in Houston into how brain cells relate to each other.

“It gives me a sense of purpose,” says Costa, 49, a native of Brazil who is now associate professor of medicine and neuroscience at the University of Colorado-Denver Anschutz Medical Campus. “It was the right purpose at the right time.”

“You have this human being in front of you,” he says, recalling Tyche’s birth. “An individual did not ask to be born—it’s your full responsibility.”

“And this person is wired to enchant and to bond with you,” says Costa, who displays photos of his daughter, wearing bangs, in his office.

In Costa’s clinical trial, young men and women with Down syndrome took memantine, normally used by Alzheimer’s patients to improve their memory, for 16 weeks.

The subjects showed statistically significant improvement in one of five key memory tests compared with others who took placebos. It was not a huge outcome, but enough to draw attention from the Down syndrome community around the world—a lengthy profile of Costa in The New York Times also won him notice—and he is now seeking funding for a broader trial.

Michelle Sie Whitten, executive director of the Global Down Syndrome Foundation, which has helped fund Costa’s research for six years, says he made a crucial link between Alzheimer’s and Down syndrome that will affect future research.

“No one, including Alberto, is jumping up and down” over the results of the clinical trial, she says, “but it showed us much more information than we had before.”

Only a handful of people are doing research into Down syndrome because funding for it is sparse, even though an estimated 400,000 people in the U.S. have the condition, she says.

A turning point in Down syndrome research was when Dr. Muriel Davisson of the Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine, whom Dr. Costa calls his mentor, created a mouse with the equivalent of Down syndrome.

Costa, who worked with Davisson for four years, began working with the mouse’s offspring, honing in on the hippocampus. “Nobody cared about the hippocampus before that,” he says.

In 2007, Costa published a study that showed giving the mice memantine could help their memory.

Costa calls the study “confirmatory,” saying that one with more patients over a longer period of time would help prove “beyond a shadow of the doubt that this is the way to go.”

Still, that hasn’t stopped parents from contacting Costa from Gibraltar, Malta, Poland, Brazil, Chile and other places, some asking whether they should give their children the drug.

He says no. It’s still an experimental drug whose long-term effects are unknown. “Hence, please don’t try it,” he tells them.

Costa attended medical school in Rio de Janeiro, where he was born. He and his wife moved to Baltimore in 1989, where he studied tacrine, a drug shown to improve the thinking of Alzheimer’s patients, at the University of Maryland.

Costa eventually moved to Denver to do research on Down syndrome at the Eleanor Roosevelt Institute. He left in 2006 to do research as an associate professor at the University of Colorado-Denver medical and graduate schools.

Tyche is now a junior in high school. She and her dad watch Japanese anime together. “She is evolving to be more and more of a friend,” Costa says with a smile.

And what does Tyche think of her father’s research? “She thinks it’s really cool.”