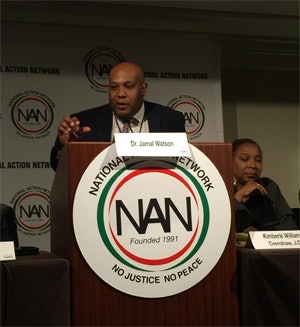

Diverse Senior Writer Jamal Eric Watson moderates a panel discussion on the “Crisis of the Black Intelligentsia.”

Diverse Senior Writer Jamal Eric Watson moderates a panel discussion on the “Crisis of the Black Intelligentsia.”Black scholars whose concern for Black America’s well being shows up in their classroom teaching, research, authorships and others aspects of their work sometimes are discouraged from following those pursuits, perhaps especially by colleagues at non-Black institutions where a Eurocentric education has long been the norm.

That was the broad consensus of several prominent African American academics—from a mix of Ivy League, historically Black and other universities—featured last week at the Rev. Al Sharpton’s annual National Action Network conference.

The panelists’ official topic for discussion was “Crisis of the Black Intelligentsia.” Under that theme, however, they tackled such wide-ranging subjects as how arguably elitist is the “public intellectual” label to how scholars and like-minded others, during the final leg of Barack Obama’s presidency, might help push politicians to address The Great Recession-driven, record-breaking decline in Black wealth and other pressing matters of Black life.

“What does racial justice look like at the end of the Obama era?” asked Kimberle Williams Crenshaw, a professor at Columbia University Law School and the University of California at Los Angeles School of Law. “Thinkers and activists and stakeholders need to put together an agenda … “

In a New York City hotel conference room brimming mainly with Blacks but also some non-Blacks from various walks of professional and community life, hers was among comments eliciting bursts of applause and, here and there, an “amen.”

It came as each of the six panelists offered their take on the triumphs and trials of being a Black scholar who views Black issues on equal par as White ones. Also, it came as the scholars shared their perspectives on the dangers of assessing people’s value based upon their academic pedigree—or lack of college degrees—their workplace and their wallet.

“I’m just a dude from Brooklyn and the Bronx doing the work,” said Dr. Christopher Emdin, a Columbia University Teachers College professor noted for his academic focus on hip-hop music and for deploying rap to teach, among other subjects, science. “I’ve been this way … I was a [Black] leader way before I had a PhD.”

Further, he said, “If there is a Black intelligentsia that means there are others [who lack intelligence]. The use of the word alone creates a hierarchy … It means you wear a certain hubris along with the [intelligentsia] title.”

“There is no crisis in the Black intelligentsia,” said Dr. Greg Carr of the Howard University Afro-American Studies Department. “There’s a crisis in whose team we’re going to play on.”

The National Action Network’s four-day conference, which kicked off April 8, took up an array of issues, including entrepreneurship, labor, police brutality, the 2016 election, the status of Black youth and Black health and the Black church’s role in black life.

The other professors on the Black intelligentsia panel were Drs. Tanisha Ford of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst Women’s Studies Department, Amos Jones of Campbell University School of Law and James Peterson of the Lehigh University Africana Studies Department. The panel’s moderator was Dr. Jamal Watson, a Diverse Issues in Higher Education senior writer and author of a forthcoming biography, “The Evolution of Al Sharpton: The Provocative Politics of the People’s Preacher.”

Among other questions, Watson asked how being an Afrocentric educator might affect such a person’s prospects for winning tenure. This, at a time of increasing reliance on non-tenured adjunct professors and when tenure seems increasingly elusive for a growing number of those who aim for it.

“That’s a tricky question,” said Peterson, as he noted the number of younger Blacks he’s hired recently. “I was committed to working in a field that kept me close to the community. I’m a literary scholar … I made the academy, in many ways, bend to my will … Now that I’m hiring young people, I’m not requiring them to be as bull-headed as I was … There’s a lot at stake.

“I say, ‘Listen, you have to do their work. But once you do their stuff, you have to do your own.’”

University Massachusetts’ Ford, the only, as yet, non-tenured panelist, said she keeps that and part of her own family’s collegiate experiences in mind as she stays committed to her focus on black women and black feminism in America.

She graduated from Indiana University, Ford said, the same campus where her mother and a handful of her mom’s fellow Black classmates, in the 1970s, got chastised for daring to even casually congregate. In South Bend, IU’s hometown, city officials also legally permitted the Ku Klux Klan to parade through city streets back then. That handed-down history lingers; it propels her, she said.

“I’m still on that tenure road,” Ford said. “I don’t have any answers. The one thing that I go back to is that I am a Black woman, and that’s a political statement in itself. I live on the front line. If you’re Black in America, you live on the front line … My work, naturally, is an extension of who I am.”

When one’s work and self are so intertwined, one can get tripped up, even if momentarily, Columbia Teachers College Emdin said. When he’d newly landed at Columbia, he was officially charged with finding a more senior, tenured faculty person to become his mentor. One of the few people whom he approached about becoming his mentor was a black man who spoke with a British accent.

“He’s got the tweed blazer on and the ‘fro is gray. I had this vision: I’m gone go into his office and he gone sit and share mad knowledge,” Emdin said.

When the same professor, as a first question, asked and got an answer to Emdin’s primary research focus, which was hip-hop’s cultural impact, Emdin said, “He looked at me and looked away. After a while, I slowly stepped away.”

Later he found out that the Black man with the British affectation hailed from Arkansas originally. “The things you [think] you have to be to be accepted by the institution. Part of that meant the tweed jacket, the British accent.”

That symbolized the kind of identity crisis and “trauma” that some Black scholars face. Part of the problem was that Columbia imposed this idea that a Black man couldn’t be authentically Black on that campus. Part of the gentleman’s problem was self-inflected, Emdin said.

And the Black scholar’s job, in part, is to challenge the unfair expectations of so lofty and vaunted a White institution as Columbia.