The shortage of guidance counselors is the latest in the ongoing fiscal crisis that has plagued Philadelphia’s public schools.

The shortage of guidance counselors is the latest in the ongoing fiscal crisis that has plagued Philadelphia’s public schools.PHILADELPHIA — As Shira Smillie begins the task of completing her college applications, it’s likely that she will not look to her school’s guidance counselor for help as she navigates the daunting process.

“I probably won’t have access to my counselor,” said the 17-year-old honors student who attends Central High School, one of Philadelphia’s best public schools.

Over the next few months, she will send off a handful of applications to a number of colleges including the University of Pennsylvania, Spelman, Howard and the University of Pittsburgh. “I’ve been proactive in getting a head start on things, but I still want to be able to talk to someone about the process. It can be confusing.”

Smillie, who will be the first in her immediate family to attend college next year, has every reason to be alarmed. In the wake of staggering state budget cuts, the six full-time counselors who had been assigned to provide services to the nearly 2,400 students at her high school has been reduced to just two, leaving Smillie and other graduating seniors with having to figure out the complicated admissions process all by themselves.

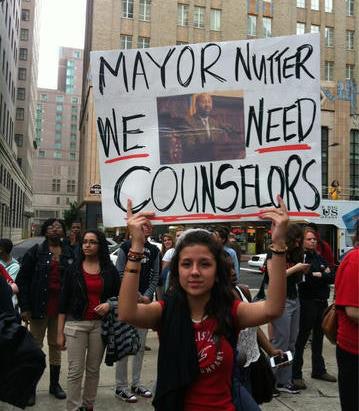

The shortage of guidance counselors is the latest in the ongoing fiscal crisis that has haunted the city’s public schools. Over the past few years, thousands of parents have abandoned the school system altogether and have opted instead to enroll their children into charter schools or relocate them to the nearby suburbs. In addition, federal budget cuts have cost the city $130 million in aid, forcing school officials to close 24 schools over the summer. More than 4,000 employees were initially laid off but were subsequently invited back to work after the state provided $50 million in emergency funds last month, shortly before the schools opened.

The librarian at Central High was not called back, and the recently renovated $5 million library, which was supported by the school’s alumni, remains closed.

“We had cut all assistant principals, all guidance counselors, all art, all music, all sports, all secretaries,” said Dr. William Hite, the school’s superintendent.

The budget slashing isn’t particular to Philadelphia. Over the last year, Chicago has also laid off 3,000 teachers and closed 49 schools, sparking dozens of protests from education advocates. In Cleveland, more than 500 teachers lost their jobs last year while, at the same time, nearly 4,000 teachers and staff in Los Angeles received pink slips.

“We really need an education movement in this country. It’s a civil rights issue,” said the Reverend Al Sharpton, who traveled to Philadelphia over the weekend to call attention to the impact of the steep budget cuts, while also lashing out at Pennsylvania’s Republican Governor Tom Corbett for orchestrating the cutbacks. “You got money, Corbett, for jails, but no money for schools. And you ask what’s wrong with the kids? I come to ask, ‘What’s wrong with you?’” Sharpton bellowed. “Bible says that you reap what you sow. Well, if you invest in jails and cut the budget on schools, you’re investing in incarceration rather than education.”

Sharpton’s comments were delivered at the day-long forum held at the Community College of Philadelphia that was organized by National Action Network, the civil rights group that he founded in 1991 and is co-sponsored by Education for a Better America (EBA), a not-for-profit organization started by his daughter Dominique to raise awareness about education disparities, prevent escalating high school dropouts and encourage health and wellness in schools.

In urban areas across the country, there has long been a shortage of guidance counselors to address the developmental issues that students face while also helping to usher them through the college admission process.

But some college admission officers at four year institutions wonder if the additional shortage might mean fewer applications — particularly among minority students.

Dr. Judith Gay, the interim president of Community College of Philadelphia who participated in the education forum, is an important stakeholder. In recent years, enrollment at the two-year college has skyrocketed, perhaps as a result of high school graduates deciding to put the bachelor’s degree on hold to prepare themselves for entry into the job market or to transition later into four-year institutions.

That’s the route that Janice Palmer said that her son Jonathan will take.

“I’m going to be honest, I don’t know much about these FAFSA forms and stuff like that, so I can’t be all that helpful to my son as I want to be,” she said. “You look to the schools to help you with these things, but they keep telling me, there ain’t no money. I just don’t understand it.”