Yuri Kochiyama joined demonstrations organized by the Congress on Racial Equality and other groups, often the only Asian American there.

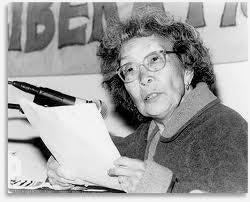

Yuri Kochiyama joined demonstrations organized by the Congress on Racial Equality and other groups, often the only Asian American there.Human rights activist Yuri Kochiyama — one of the most visible Asian Americans to fight alongside Blacks for equality in the 1960s and an ally of Malcolm X who comforted him as he lay dying — has died. She passed away in her sleep Sunday at age 93 in her Berkeley, Calif., home.

Kochiyama is perhaps most famous for cradling Malcolm X’s head in her lap as he died from gunshot wounds in 1965, an image captured in a Life magazine photo. She had been attending his appearance at New York City’s Audubon Ballroom when an assassin shot him, and she rushed to the stage. A Life magazine photo showed her fear.

A University of California, Santa Barbara professor of Asian American studies, Dr. Diane C. Fujino authored a biography titled “Heartbeat of Struggle: The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochiyama.”

In a 2006 interview for Diverse, Fujino noted that “every Black radical and nationalist I’ve met embraces Yuri, and young Asian Americans learn about someone who looks like them, but has worked completely outside the system.”

The daughter of Japanese immigrants, Kochiyama was born Mary Yuriko Nakahara and grew up with her brothers in a White neighborhood in southern California.

But after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941, everything changed.

FBI agents arrested Kochiyama’s father in a mass roundup of “suspects” and jailed him based on national security paranoia. He was denied medical care, and, shortly after his release, he died. The rest of the family were among 120,000 people of Japanese descent, most of them U.S. citizens including Kochiyama, who were herded into remote internment camps during World War II. Among other things, the ordeal cost the overwhelming majority of internees their homes, jobs and nearly everything they had owned prior to their imprisonment.

While at the camp, Kochiyama met and fell in love with Bill Kochiyama, a decorated veteran of the famous 442nd Regimental Combat Team, an all-Japanese American unit of the U.S. Army. After the war, they married and moved to Bill’s native New York City, where the only apartments they could afford were in Black and Puerto Rican neighborhoods. In 1960, they moved to Harlem, where Yuri Kochiyama learned about Jim Crow laws of the South from co-workers and friends. She saw parallels between the segregation of and discrimination against African Americans and what her family had endured in the internment camps. In the course of fighting for racial justice, she cultivated deep ties with countless Blacks.

While raising her children, Kochiyama joined demonstrations organized by the Congress on Racial Equality and other groups, often the only Asian American there. Blacks respected and appreciated her behind-the-scenes work, such as writing newsletter articles or distributing fliers door-to-door. In 1963, she met Malcolm X, whom she has called “the most inspiring person in my life.” She began attending his Organization of Afro-American Unity Liberation School, where she learned the history of colonialism in Africa and the slave-trade economy. Less than two years after their first meeting, Malcom X was assassinated.

But by that time, Kochiyama had begun to share his Black Nationalism vision and got involved with the Republic of New Africa, which called for an autonomous Black nation in the southern United States. In the late 1960s, she began calling herself Yuri, a shortening of her Japanese middle name, coinciding with many Black activists taking African or Islamic names.

As authorities arrested many of Kochiyama’s fellow activists, she wrote letters to political prisoners, organized events for their defense and attended court hearings in support. She was often the first person whom prisoners would call upon their release.

Kochiyama was a mentor during the Asian American movement that grew out of Vietnam War protests. Younger activists sought her out for her ability to connect Black and Asian issues.

She was also actively involved in the push for ethnic studies, redress and reparations for Japanese Americans, Puerto Rican independence and many other struggles. She became a frequent speaker on U.S. college campuses, where she promoted Asian-African solidarity.

In 1998, Kochiyama was a scholar-in-residence at the University of California, Los Angeles. The UCLA Asian-American Studies Center also houses some of her personal papers, and its staff members worked with her on the 2004 publication of her memoir, “Passing It On.”

“We are grateful to be part of preserving Mrs. Kochiyama’s legacy for future generations,” said Dr. David Yoo, the center’s director. He added his hope that she “rest in power and peace.”

At the University of Massachusetts Amherst, a student-managed community space within the Asian American learning resource center is named for Kochiyama. The space supports cultural and education programming.

Kochiyama, whose husband died in 1993, is survived by four children, nine grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.