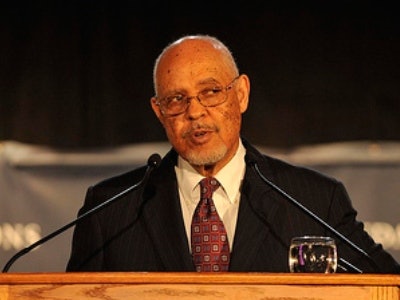

James A. Joseph is a professor emeritus at Duke University and chairman emeritus of the board of the Foundation for Louisiana. (Photo courtesy of Duke Photography)

James A. Joseph is a professor emeritus at Duke University and chairman emeritus of the board of the Foundation for Louisiana. (Photo courtesy of Duke Photography)Whether he was helping to organize the nascent civil rights movement in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, or touring South Africa in the grips of apartheid in the 1970s, Ambassador James A. Joseph had a knack for finding himself in places at the cusp of momentous social change.

Joseph says that a friend of his sums up his life thusly: “It’s interesting to see that wherever you were, you were always a troublemaker.”

For his part, Joseph denies that the sobriquet of “troublemaker” is a perfect fit. “I don’t call myself a troublemaker, any more than the Greek philosophers or Hebrew prophets were troublemakers,” he says. “They were strong advocates of change and they were seeking to improve the quality of life for people. That’s what I’ve always tried to do and what I do now.”

Joseph’s life story is in some ways an almost perfectly realized expression of the American success story. Born in Louisiana’s rural Cajun country, Joseph has lived a life filled with honors: serving as the U.S. Ambassador to South Africa in the 1990s, and enjoying high-level positions on foundation boards, in university leadership and in four presidential administrations.

As ambassador to South Africa from 1996 to 2000, he was witness to a country in the midst of the truth and reconciliation process, which sought to begin to heal the wounds of apartheid. In that capacity, Joseph was the only U.S. ambassador to present his credentials to the legendary Nelson Mandela.

His career momentum got its start at Southern University, where he joined the ROTC. After completing his military assignments, Joseph, who is the son of a minister, moved on to Yale Divinity School. His next step was a teaching and administrative post at Stillman College in the 1960s.

At the time, Tuscaloosa was home to a large Ku Klux Klan presence, meaning that Black citizens of that area were subjected to a deep terror that hindered the progression of the civil rights movement.

“In Alabama, the political mood seemed more threatening, the prejudice stronger, and the Klan meaner,” Joseph writes in his recent autobiography, Saved for a Purpose: A Journey from Private Virtues to Public Values.

Nevertheless, fortified by his ideals and commitment to justice, Joseph helped start the civil rights movement in the area. His work was not without its perils. He and a friend were once trapped in their parked car while some Klansmen surrounded them, rocking the car back and forth. Yet Joseph was undaunted and his activism there was to set the standard for the rest of his varied career.

The relentless pace of Joseph’s life has relaxed now — he is a professor emeritus at Duke University and chairman emeritus of the board of the Foundation for Louisiana, established to help the state after Hurricanes Rita and Katrina — but he does not rest easy on his laurels. As he sees it, the torch still needs to be carried on. Some of the social and ethical victories won in the 1960s are not yet wholly secure. Joseph points to the decline in social mobility as a major cause for concern, as well as attempts to roll back the Voting Rights Act in some states.

“In the 1960s we had a revolution of the so-called underprivileged. Now we have a counterrevolution fueled and financed by a select group of the overprivileged,” Joseph tells Diverse. “That counterrevolution intends to dismantle the progress that we made as a result of the initial revolution in the 1960s. Many of [those engaged in this counterrevolution] occupy status and standing in society and are respectable people. Yet they don’t really understand the importance of the changes that occurred that they are now trying to unravel.”

In many ways, the struggle for racial equality and justice lives on in the form of a new generation of student protesters and the Black Lives Matter movement. Joseph points out that criticisms of Black Lives Matter have historic parallels in the charges levied against groups like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

“The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in the 1960s was considered by many other groups to be too militant,” Joseph says. “People came to recognize, at least within the African-American community, the importance of groups like SNCC in the 1960s, just like they are coming to recognize the importance of groups like Black Lives Matter in the period in which we now live.”

As a university professor, administrator and chaplain, Joseph has had many brushes with student protests and countercultures.

“The Black Lives movement has certainly created a new consciousness of the many insidious impediments to progress for Black people,” Joseph says. “It’s not just individuals who are racist. Institutions can be equally biased. I think they have been very successful in pointing to institutional racism.”