If you’re in the habit of spewing negative statistics about the education of Black students in the United States, expect to draw the ire of Dr. Ivory A. Toldson.

In fact, you can expect Toldson to call “BS” – his acronym for “bad statistics” – if you create, cite or repeat a negative statistic about Black students without taking a broader look at whether the statistic is based on accurate data or fails to take into account contributing factors and conditions.

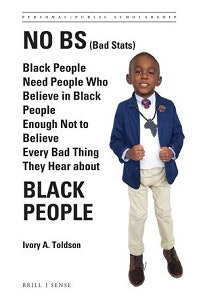

That much is clear from No BS (Bad Stats): Black People Need People Who Believe in Black People Enough Not to Believe Every Bad Thing They Hear about Black People, a new book in which Toldson tackles a range of misconceptions and myths related to Black educational progress. The topics range from whether or not enrollments at HBCUs are declining to how Black students are not actually “underrepresented” in higher education as a whole – thanks in large part to their enrollment in community colleges, online universities and for-profit colleges – although they are underrepresented when it comes to competitive universities.

Above all else, the book is a clarion call to “humanize” the data in the public discourse about Black students in order to remove the stigmatic effect of negative reports, which Toldson says can lead educators – and Black students themselves – to expect failure instead of searching for their strengths.

“The purpose of education should be to reveal talents, not to expose weaknesses,” Toldson writes. “Unfortunately, many Black students only go to school to learn what they do not do well. They learn that they are bad test takers, slow readers, not a ‘math person,’ or have a short attention span.”

Toldson seeks to uproot the “paradigm of the achievement gap, which conditions us to separate high achievers from low achievers on a uniform measure.”

“Reconditioning educators and educational researchers to discover diverse talents among diverse students would not simply ‘close’ the achievement gap,” Toldson writes. “It would render the nomenclature of the achievement gap irrelevant and obsolete.”

Toldson is in a unique position to speak on the plight of Black students in the United States.

In the book, he recounts his own experience as a 4th-grader who was branded as a “slow learner.” He recalls daydreaming in class and believes he would have met the criteria for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder as a child.

But as the young Toldson daydreamed, he also did a peculiar mental exercise in which he would give the numbers 1 through 10 a gender and a personality as boys, girls, teens, men and women.

The story might just be an odd childhood memory if Toldson wasn’t now on a mission to get researchers to take a more humanistic approach with their statistics.

“Today, researchers routinely separate numbers from people,” Toldson writes. “We use deficits statistics, test scores, achievement gaps, graduation rates, and school ratings, without a humanistic interpretation.”

When it comes to making sense of lower test scores in reading or higher dropout rates for Black students, the context and conditions – and the proper calculations – are essential, Toldson argues.

For instance, Toldson says proper calculation of the dropout rate is poorly understood and often misrepresented in even well-meaning propaganda meant to prompt action, such as a billboard in Washington, D.C. that proclaims 57 percent of students in the district drop out.

“To be blunt, the message on the billboard is a lie, and technically, the percent of students that drop out has only a little to do with the percent that graduate,” Toldson writes, explaining that many Black parents may take their children out of the district to attend school in an outlying area, which ends up technically worsening the graduation rate in the school district from which they left.

Much of Toldson’s book is a compilation of social media posts in which he commented on particular reports with which he found fault. Or things he has already dealt with in years gone by, such as the “myth” that there are more Black men in prison than in college.

But just as Toldson admonishes readers to be more cautious about negative statistics concerning Black students and their educational ability and achievement, readers would be wise to take the same tact with Toldson’s book.

For instance, Toldson claims that the line about there being more Black men in prison than college was “invented” by a white man named Vincent Schiraldi. Schiraldi, a juvenile justice policy reformer at Columbia University, however, told Diverse he owes the credit to someone else, Tom Mortenson, a higher education policy analyst. And neither man could explain how Ice Cube — the legendary rapper from California – beat them both to the punch when he recited the line in a lyric in 1990, long before both men published their work on the issue several years later.

Shortcomings aside, No BS is still a provocative work and an invaluable resource. It will undoubtedly push readers to question the onslaught of negative statistics they hear about Black students and even examine their own personal biases that might lead them to doubt statistics about Black students when the statistics actually say something good.

Jamaal Abdul-Alim is the education editor at The Conversation.

This article will appear in the March 21, 2019 edition of Diverse.