Those were persistent themes Tuesday at “Strategies for Increasing Graduate Program Diversity,” a day of speakers, sessions and panels at American University presented by Educational Testing Service in collaboration with the Council of Graduate Schools.

The event assembled academics and other higher education leaders to discuss pressing and complex issues and how to move from talk to action at the personal and institutional level in ways that are grounded in data and research, reflect creativity and extend beyond the classroom experience.

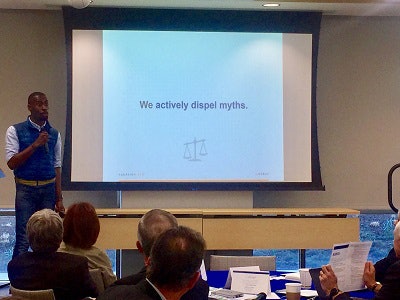

DeRay Mckesson, an activist and former school administrator in Minnesota and Maryland, suggested in keynote remarks that the conversation about inclusion of underrepresented groups needs to be changed from a common student-deficit narrative that occurs “when people who aren’t close enough to the content become people who tell the stories about the world we live in” and reinforce an unsatisfactory status quo.

DeRay Mckesson

DeRay Mckesson

Drawing on experiences with diverse student populations in education administration at primary and secondary levels, Mckesson laid out 10 success strategies, including defining terms, actively dispelling myths, not compromising on values and beliefs and understanding that diversity is not shorthand for good intentions and low quality.

“Part of our work, especially in the diversity space, is to be very clear about what our values are and be unwavering about them,” Mckesson said.

It’s equally important to work from a common vocabulary and fundamental understanding of certain realities, he said. For example, it is the educational institution, not the student it serves, that is deficient, and diversity is not the same as inclusion, he said.

“Diversity is easier than inclusion,” Mckesson added. “Inclusion is about changing culture. It’s harder.”

Enhancing inclusion and equity also means creating entrances and on-ramps for underrepresented students and overinvesting to compensate for chronic under-investment in capable students who have experienced inequities through no fault of their own, he said.

“That’s not giving an unfair advantage. It’s correcting for an unfair disadvantage.”

Similar themes were echoed in a panel about best diversity and inclusion practices to improve the grad school experiences of minoritized and marginalized groups.

Earning a master’s or doctoral degree is stressful and challenging, but minority and first-generation students in majority settings have added burdens ranging from imposter syndrome to feelings of isolation, said Dr. Elizabeth Ortiz, vice president of the National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education (NADOHE) and vice president of institutional diversity and equity at DePaul University.

Panel during the Strategies for Increasing Graduate Program Diversity Symposium

Panel during the Strategies for Increasing Graduate Program Diversity Symposium

“And then you have the institution’s inability to recognize their assets,” she said. “They’re always seen as a problem to be solved. Or they are deficient or were done a favor. Not just microaggressions, but ‘macroassaults’. We need to step back and change our attitudes. There’s not a deficient student. There’s a deficient system.”

The conditions leave affected students not just isolated, but “disenfranchised,” said panelist Dr. Renetta Tull, associate vice provost for strategic initiatives at the University of Maryland, Baltimore and the newly appointed vice chancellor for diversity, equity and inclusion at the University of California, Davis.

An attitude of student supportiveness has to exist at the highest levels and be reinforced among faculty and everywhere on campus, she said, but “wherever it starts, there have to be committed people working together, and really moving the mission forward in an intentional way.”

Among the ways to do that are determination at an institutional level to reach out and create partnerships to recruit a diverse student body, tailor admissions practices to attract such students, and address larger systemic problems within institutions that hinder student persistence such as lack of faculty diversity, said Dr. Victor Saenz, vice chair of the American Association of Hispanics in Higher Education and an associate professor in the department of educational administration at the University of Texas – Austin.

He agreed with Ortiz that elitism and implicit bias at some schools often deprives qualified underrepresented groups of opportunities to be grad students – or teachers – on some campuses.

“The snob factor is real,” said Ortiz. “Lots of pathways are obscure for underrepresented students, many of whom are first-generation students of color. Faculty should engage with diverse communities; go out and be proactive about finding talent.”

The negative effects of implicit bias on diversity and inclusion efforts were mentioned several times, and Dr. Bentley Gibson led an interactive session on how everyone can uncover and mitigate their own unconscious prejudices.

Those prejudices, held overwhelmingly by the majority of people across racial lines, generally mean more positive views of White people and more negative views of Black people – associations that have implications for diversity, inclusion and equity in graduate programs.

“Talk about systems and structures and institutions is important,” said Gibson, an associate professor of psychology at Georgia Highlands College and founder of The Bias Adjuster LLC. “But my talk is about the individual. Organizations are made up of individuals. Our biases affect how we relate to other people. What is the power of associations we have been making since childhood? And how do we counteract it?”

Solutions – which also can be applied to implicit biases about gender, sexuality, and age, Gibson noted – include not framing people in terms of deficiencies and negativity; thinking about counter-stereotypic images and realities; and shifting group boundaries by getting diverse people together to work on the same team.

LaMont Jones can be reached at [email protected]. You can follow him on Twitter @DrLaMontJones