Earning their doctorates in the 1930s, ‘40s and ‘50s, Black scholars were slowly welcomed into White institutions where they then combined academia with activism.

Dr. David Canton, associate professor of history at Connecticut College, is working on a biography of Dr. Lawrence D. Reddick, which will focus on the mid-20th century when an increasing number of African Americans earned doctorates and entered the faculties at predominantly White colleges and universities (PWIs).

Dr. David Canton

Dr. David CantonCanton refers to Reddick and his contemporaries, including Dr. St. Clair Drake, Dr. W. Allison Davis, Dr. Ralph Bunche and Dr. Adelaide Cromwell, as the second generation of Black scholars. While the names of the first generation of Black professional scholars — Dr. W.E.B. DuBois, Dr. Carter G. Woodson and Dr. Charles H. Wesley — are well known and studied, this second generation often exists in the background. In fact, Dr. David A. Varel titled his biography of Davis, who was the first African American person to receive tenure at a PWI, The Lost Black Scholar.

“These phenomenal and often unsung scholars played a vital role in teaching Black history and helping to shape and mentor the subsequent generation of Black academics,” says Dr. Robert T. Palmer, department chair and associate professor of educational leadership and policy studies at Howard University. “I hope that we can be more intentional in making these and other Black pillars a household name.”

History

Canton says his research shows that, prior to 1930, 51 African Americans had earned Ph.Ds. Between 1930-43, more than 300 African Americans earned Ph.Ds. Among them was Reddick, who in 1937 wrote an article titled “A New Interpretation for Negro History,” in which he asked historians to approach African American history by combining social history with economics.

Most of these scholars taught at historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs). In the 1940s, African American scholars began being hired at PWIs—but usually only one per institution and often as adjunct faculty.

The exception was Davis, an anthropologist, who was hired in 1942 at the University of Chicago with a full faculty position, earning tenure in 1947. Davis did not shy away from complex topics; Varel’s biography describes Davis’ groundbreaking investigations into inequality, Jim Crow and the cultural biases of intelligence testing.

“By allying with prominent White social scientists, he ensured that his work would reach a mainstream audience,” says Varel, who is currently affiliate faculty at Metropolitan State University of Denver. “His appointment at Chicago demanded a fight by some sympathetic White Chicago scholars and philanthropists who wanted to break the Jim Crow hold on White university faculties.

“Davis’ remarkable accomplishments, the way his research agenda fit in perfectly with Chicago’s interdisciplinary

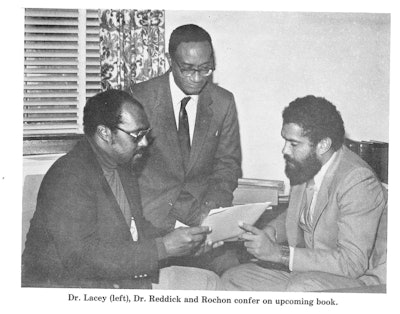

Dr. Lawrence D. Reddick, middle, confers with colleagues

Dr. Lawrence D. Reddick, middle, confers with colleagueson a book project.

tradition and a changing context during and after World War II ultimately made his tenured professorship possible,” he adds. “Even so, very few other Black scholars won such appointments for another generation.”

In the article “The First Black Faculty Members at the Nation’s Highest-Ranked Universities,” published in The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, author Robert Bruce Slater details African American scholars who taught at elite institutions. Harvard University had a Black faculty member as far back as 1870 and it was there that DuBois and Woodson earned their doctorates. The University of Pennsylvania and Brown hired African American faculty in the 1940s.

The article notes that Bunche earned tenure at Harvard in 1950. That same year, J. Saunders Redding received tenure at Brown and 20 years later did so at Cornell.

Not noted in the article is Cromwell, a sociologist who died last year at the age of 99, the first African American woman to be hired at a PWI, working at Hunter College and Smith College. She joined the faculty at Boston University in 1951. Two years later, she founded BU’s African Studies Center and in 1969 founded the African American studies program at a time when PWIs were being pressured by students to diversify their faculties.

Impact

“These early Black scholars—similar to Jackie Robinson or any early pioneers—faced racism and microaggressions,” says Canton. “These scholars who studied inequality built up the fortitude to engage that and looked at the bigger picture.”

Reddick didn’t earn tenure until 1970, after working three years as an adjunct at Temple University. He was 60 years old. Canton says universities understood they had to change the narrative of racism, noting Reddick’s tenure position was due to student activism.

Dr. David A. Varel

Dr. David A. Varel“Changing the narrative of racial stereotypes starts with academics, ideas and how they filter through textbooks, K–12 curriculum, TV and media to change the perception of how Blacks are viewed in this country,” says Canton. “Reddick was very engaged in fighting racism in textbooks.”

Reddick’s career began at Dillard University, an HBCU. From 1939-48 he was the curator at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York. During that time, he was responsible for preserving 19th-century Black newspapers on microfilm. He also held classes on African American history, with DuBois and Woodson among the speakers.

“He used the Schomburg as an institution to promote Black history and culture,” says Canton. “Also, Reddick was a believer in the impact of the arts. He supported the American Negro Theater … Reddick understood the connection between history and culture and how that reaches and changes people’s perceptions.”

Reddick and his contemporaries felt an integral connection between academia and activism.

“[Davis] invested fully in the role that intellectuals like him had in galvanizing social change,” says Varel. “This meant choosing research topics that were important to the larger Black freedom struggle … These activities helped grassroots activists better understand the struggle, and they helped win over some White people to the cause.”

Contemporary Relevance

“The work and influence of these scholars had a profound impact on the teaching of Black history at PWIs,” says Palmer. “For one, it helped to provide a broader reach of the teaching of Black history and it also helped to expose more White students to Black history. Finally, I think these and other scholars helped PWIs realize that much like European history, the preservation and teaching of Black history matters.”

A colleague of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Reddick was an eyewitness to history, writing the book Crusader Without Violence: A Biography of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1959. Then, in 1965, Reddick wrote Worth Fighting For: The History of the Negro in the United States During the Civil War and Reconstruction, a book he intended for high school teachers.

However, as White historians became interested in studying slavery in the 1970s, Reddick grew concerned, says Canton. He didn’t want to see Black scholars or HBCUs pushed to the background. Throughout the 1970s and ‘80s Reddick saw HBCUs hit with a “brain drain,” as some scholars who had taught at these institutions became affirmative action hires at PWIs. At the end of his career, Reddick returned to Dillard.

“Reddick was also concerned about archives,” says Canton. “[HBCU] research libraries should be the location of these archives. When an institution wants to buy a collection of people’s papers, who has the resources and the space to maintain that important information? Reddick said it should be at HBCUs.”

Most of Reddick’s papers are at the Schomburg, which currently has a grant to organize them into a researchable archive. These valuable documents will provide insights into how these second generation Black scholars worked with each other and served as mentors. Their work resonates with scholars today, and Canton says those who don’t understand the history are not prepared for the present.

“Yes, we’ve made progress, but there is still institutional racism,” says Canton. “How do we get from equality to equity? We look at structure. That’s what I do in my classes.”

This article appeared in the Feb. 6, 2020 edition of Diverse.