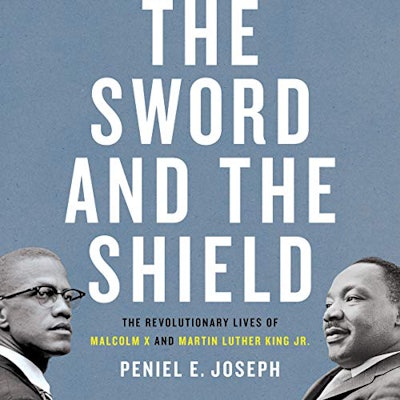

Dr. Peniel E. Joseph’s The Sword and The Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. could not have been published at a more apropos time.

As the nation witness around-the-clock protests following the horrific deaths of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and countless other unarmed Black men and women killed at the hands of police officers and White vigilantes, Joseph provides readers with a historical blueprint on how two of the nation’s most prominent Black leaders of the 1960s — Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X — navigated the political and social terrain of their era.

Despite the tendency to pit the two men against one another — similar to how historians tend to compare Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois to Booker T. Washington — Joseph informs the readers that Martin and Malcolm were deeply aligned on many goals and opinions, albeit their tactics and public personas may have been different.

Their young widows — Dr. Betty Shabazz and Coretta Scott King — even developed an abiding friendship and sisterhood that continued decades after their martyred husbands were killed by assassins’ bullets before either one of them turned 40.

It is no coincidence then that Joseph begins The Sword and The Shield with the widely circulated black and white photo of Martin and Malcolm on Capitol Hill smiling and shaking hands on the national stage. On that day — Thursday, March 26, 1964 — U.S. senators were debating the pending civil rights bill that had faced serious opposition.

Dr. Jamal Watson

Dr. Jamal Watson“What I wanted to do was get behind the photo and talk about these men converging at different crossroads in their lives,” says Joseph in an interview.

For Malcolm, that crossroad is going beyond the Nation of Islam, becoming a human rights, secular political figure and a global faith leader who is anti-colonialism, anti-imperialism and who offers a critique of capitalism and a pursuit of Black radical dignity at the global level, says Joseph.

For King, that crossroad is best symbolized by his ongoing emergence as a global figure who comes to the U.S. Senate on that day as Time magazine’s “Man of the Year” and who is a few months shy of winning the coveted Nobel Peace Prize.

“I wanted to see both of them as activists, intellectuals,” says Joseph, adding that both men were policy activists, adding that Malcolm, in particular, was on a variety of political boards until Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad made him stop. “So, when we think about King and Malcolm X, they’re interested in anti-racist policies as well as ending institutional racism.”

That rare historic meeting on Capitol Hill — the first and only time that the two men would physically meet and converse — illustrates how Martin and Malcolm were deeply concerned with transforming democratic institutions and how their presence reinforced a strong commitment to a radical form of civic engagement.

“We think of them as sword versus shield but they’re really both,” says Joseph, who holds the Barbara Jordan Chair in Ethics and Political Values at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs and is a professor of history and founding director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at the University of Texas at Austin. “One of the reasons I wrote the book is that I didn’t want people to think you had to be team Malcolm or team Martin. We really need to be both.”

Unlike other comparative biographies on King and Malcolm X, Joseph brilliantly shows the impact that each man had on the other. “King is influenced by Malcolm and Black power,” Joseph notes, “just like Malcolm is influenced by King and King’s movement.”

Joseph calls Malcolm X the “boldest truth teller against White supremacy.” That mantle gets passed along to King after Malcolm is killed in 1965.

Still, Joseph does not bypass the stark ideological and political differences between the two. Each man is shaped in large part by their upbringing. Malcolm’s emergence as the leading Black working-class hero and political activist of the 20th century is connected to his humble beginnings in Omaha, Nebraska and later Lansing, Michigan.

Long before the Black Lives Matter movement, there was Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), and Malcolm’s father — who was later murdered by the Ku Klux Klan — was an active member. As a young boy, Malcolm attended UNIA meetings where attendees pushed for Pan Africanism and Black nationalism in the United States and across the world.

King, in contrast, was born to an upper middle-class Atlanta family. The son of a preacher, he honed his oratorical skills at a young age and eventually enrolled at Morehouse College at the age of 15 before continuing his studies at Crozer Theological Seminary and Boston University. Over time, he saw much more hope for racial reform and believed, as Joseph notes throughout the book, that America’s racist society can be altered through public policy and moral persuasion.

“They are going to evolve and broaden their scope over time which is really what’s most striking about them,” says Joseph. “These two did not stay stuck. The more people they meet, the more places they travel, the more books they read, the more experience they get and it broadens them.”

They are also competitive with each other. As King comes to see nonviolence as muscular and a preferred tactic, Malcolm was quick to pounce, often engaging in name-calling that got personal.

“They are in each other’s head, responding to one another,” says Joseph, whose 373-page book provides a scholarly framework and historiography to how we can more accurately teach, research and think about the legacy of King and Malcolm X.

“I want people to understand the story and see the story as not quite as simple as people have been telling,” says Joseph, adding that, as a youngster growing up in New York City, he was taught that King was simply a nice guy and that Malcolm X was the more rebellious figure. That narrative, he asserts, is overly simplistic. Yet, it endures.

“He’s not just the nice guy,” Joseph says of King. “He’s the guy speaking truth to power, organizing poor people, organizing Black people and organizing a human rights campaign that’s anti-war, anti-racist, anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist.”

Joseph’s book has rightly received widespread praise since its release in April.

“Arguing against facile juxtapositions of the political philosophies of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, Peniel Joseph has written a powerful and persuasive and re-examination of these iconic figures, tracing the evolution of both men’s activism,” says Dr. Henry Louis Gates Jr., of Harvard University.

Dr. Jamal Watson is Editor-at-Large. You can follow him on Twitter @jamalericwatson

This article originally appeared in the June 25, 2020 edition of Diverse. You can find it here.