When the University of Washington became the first major U.S. campus to close its doors due to the global COVID-19 outbreak on March 6, almost no one could have predicted the pandemic would have swelled to the massively widespread proportions now disrupting higher ed across the country.

Dr. Sheldon Jacobson

Dr. Sheldon JacobsonAs of Oct. 22, The New York Times had recorded more than 214,000 positive cases of COVID-19 at over 1,600 college and university campuses across the country. According to the publication’s tracker, there have been over 75 COVID-related deaths on college campuses since the pandemic started.

The response to COVID-19 has been mixed this fall. Some campuses, like the Atlanta University Center institutions in Georgia and the entire California State University system, pulled back in-person instruction and moved totally online. Others moved forward with in-person instruction but found themselves having to scale back amenities and implement social distancing protocols on campus. Roughly 60% of institutions across the country chose to re-open their doors to students for the fall 2020 semester, many with modified academic calendars that end the semester at Thanksgiving. Other institutions, including Harvard and Princeton, have opted for hybrid models that welcome some students back to campus, while having others continue their learning online.

As institutions continue to navigate the best ways to serve students amid these unprecedented times, experts warn that higher ed leaders should be bracing themselves for a second wave of the pandemic in

Dr. Sheldon Jacobson, a founder professor of computer science and director of the Simulation and Optimization Laboratory at the University of Illinois-Urbana Champaign, points to the surge in cases happening now, particularly in the Midwest and places where localities have not adhered to the guidelines set forth by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“The numbers that I’ve been running for the country have been frighteningly large,” says Jacobson, who expects December, January and February to be particularly brutal as students go home for winter break and then return to campus. “The challenge is when it starts to spread into the community — in Ann Arbor, for instance, where the number of university cases overtook the number of county cases.”

COVID-19 cases among college students

On Oct. 20, the University of Michigan and the Washtenaw County Health Department issued an emergency 14-day stay-at-home order for students after local officials noticed “an increasing trend in cases that [was] quite disturbing,” according to Washtenaw County Health Officer Jimena Loveluck.

The University of Michigan’s 628 reported cases accounted for 60% of all local cases, and, of those, 99% of the cases were between the ages of 18 and 21, which suggests to Loveluck and other county health officials that activities in residence halls and “congregate housing facilities,” like sorority and fraternity houses, are largely responsible for the surge.

Despite mask mandates, an increased awareness of hand hygiene and social distancing efforts, Loveluck says, “Sometimes even with all the layering of those good public health prevention strategies, we see that it’s not enough.”

She notes that there hasn’t been a rise in hospitalizations or deaths, which Jacobson also observed, calling cases on college campuses “just noise in the system” because of the relatively low death rates among students, many of whom are asymptomatic.

“What makes COVID-19 so difficult is not the fact that you die from it, because people die from a lot of things,” Jacobson says. “More of them will die this year from accidents than from COVID-19.”

While it is true that there have been only two reported deaths among students, Jacobson concedes that “once you get past 65, the risks really skyrocket.”

The passing of a college president

But former Florida Supreme Court Justice James Perry, chair of Saint Augustine’s Board of Trustees, cautions against diminishing the impact of the pandemic by playing what he calls “a numbers game.”

“If you value life, all life is precious and special and you don’t want to sacrifice anyone’s life. It’s not a

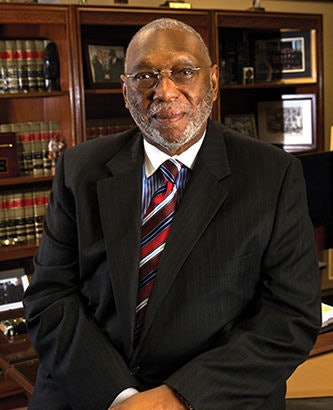

Dr. Irving Pressley McPhail

Dr. Irving Pressley McPhailnumbers game. You’re talking about life,” says Perry, whose campus was recently rocked by the death of its president, Dr. Irving Pressley McPhail, who died Oct. 15 after contracting COVID-19.

McPhail was just settling into his first semester as president of the small historically Black university in Raleigh, North Carolina, and Perry says he had already begun to build rapport with the students and had implemented a social contract, in which students agreed to adhere to the mask and social distancing requirements. Violators would be sent home.

“We’ve tried to instill into our students that it’s really not about them, it’s about protecting the other person. And they’ve bought into it,” says Perry, who likens the need to adhere to COVID-19 protocol to driving on a two-lane highway. “It’s a frightening proposition for everyone. You’re depending on the other guy to stay in his lane.”

McPhail had been called the university’s dream president when he accepted the job, and Perry says his death has particularly impacted the close-knit campus community.

“Students looked up to him, and they related to him,” says Perry. But McPhail’s passing, while tragic, hasn’t changed the way he thinks about the pandemic, Perry says. “It is very dangerous now, it was very dangerous then and it will continue to be dangerous until we can get to some kind of vaccine.”

James Perry

James PerryJacobson says the uptick in cases around the country is partially because of more testing, but also because the virus is spreading, particularly among 18- to 29-year-olds. “University students can be the super spreaders,” he says. However, data has shown historically Black colleges and universities have experienced fewer positive cases, which some experts attribute partially to the institutions’ stricter social rules — the St. Augustine’s COVID-19 compliance contract is an example — and students’ increased understanding of the disproportionate impact the disease has on communities of color.

For Perry and the St. Augustine’s administration, McPhail’s death has become a rallying cry for students to do the right thing and sacrifice individual comforts for the collective good.

“Every time you wear the mask, think of him. Every time you don’t wear it, think of him,” Perry says the campus has told the students.

Jacobson says university leaders should embrace the idea that “every crisis is also an opportunity” and encourages leaders to think strategically about “applying the same kinds of ideas to personalized education that we do to personalized medicine” in order to provide students with an educational experience that translates better into the virtual world than the prevalent model of simply moving lectures online.

“We’re getting better, but we haven’t arrived anywhere,” he says. “How can we deliver an education as well as the experience of education — how do you translate that into the virtual world?”

This requires a shift in thinking from seeing the pandemic as something to be evaluated on a month-by-month or nine-week basis to something that might be here to stay awhile, he says.

“Everyone is tired of wearing masks, everyone is tired of social distancing, but we’re not through with this,” says Jacobson. “My models suggest that we’re going to be going through this through the end of the summer 2021, and there will be over 500,000 deaths. We’re talking about starting to get into the 40-70% of the population being infected before this is all over.”

This article originally appeared in the November 26, 2020 edition of Diverse. You can find it here.